From Recrimination to Recovery

Transcript of webinar (2023). Scoot to the bottom to watch the video if you prefer

Introductions:

Naomi:

Welcome. Thanks very much for joining us. I'm Dr Naomi Murphy and I'm a Consultant Clinical and Forensic Psychologist. And this is Des McVey, who's a Consultant Nurse Psychotherapist. And it's really great to see so many people here. But it's kind of bittersweet because whilst we want to be able to offer something that's genuinely helpful to a community who've often made very big sacrifices to protect others, there's also something a bit tragic and sad about the fact that there are so many people that this presentation has resonated with. We want to provide something that is genuinely useful and so we'd be really grateful for any constructive feedback afterwards. (You can post this below in the comments). Let us know the things that worked well and were useful and also if there’s anything that’s unhelpful.

Des McVey [00:00:57]:

Hello. I want to touch on why we think we're well placed to run this workshop. As Naomi says, we're both mental health professionals and we've got training in several psychotherapy models. We've spent many years working in forensic environments where there's always the dynamics and emotions of fear and power and it's often a very toxic environment. There's a combination of hierarchies. Often in these institutions, a hierarchy of competence is usurped by the hierarchy of power, which can over spill into tyranny and fear. Both of us have in excess of 15,000 hours of delivering therapy to victims of trauma. Often the people we've worked with have been severely traumatised as children and not surprisingly, as children, alot of these people did speak out. They raised the issues, often running away from homes and telling the police that they were being abused, but only to be taken back to the homes and punished or abused even more. And I think there's a salient issue for these patients we’ve worked with where they weren't listened to. Especially with all the disclosures of abuse in children's homes. Alot of these people were at those homes and feel that they could have been listened to.

We've worked in both the private and the public sector, in prisons, in hospitals and in community services. And at times we've had to speak up and that's gone really well and at other times we've spoken up and we've been exposed to what Jacqueline Garrick refers to as a "toxic tactics", which we will talk a little more about later. So both of us have had to overcome the trauma of speaking up and being recriminated against.

Working through that process, we've developed a lot of insight into the experience, how this can manifest as a trauma, how it manifests emotionally, psychologically and in the body. And we strongly believe that a lot of people end up stuck in this psychic trauma and find it hard to find a way out.

Naomi Murphy [00:03:08]:

There is hope. Through working with a number of people who’ve experienced recrimination in private practice we have seen that no matter what sector or industry people work in, there are real similarities that cut across the across the board. So working with people in finance and business, working with elite athletes, working in health, working in social care, manufacturing, we hear all the same kinds of stories from people no matter what sector they're working in. There are at times some slight nuances depending on the sector, that is specific to that sector. But actually, there are an awful lot of similarities.

Is it really necessary to heal after speaking up?

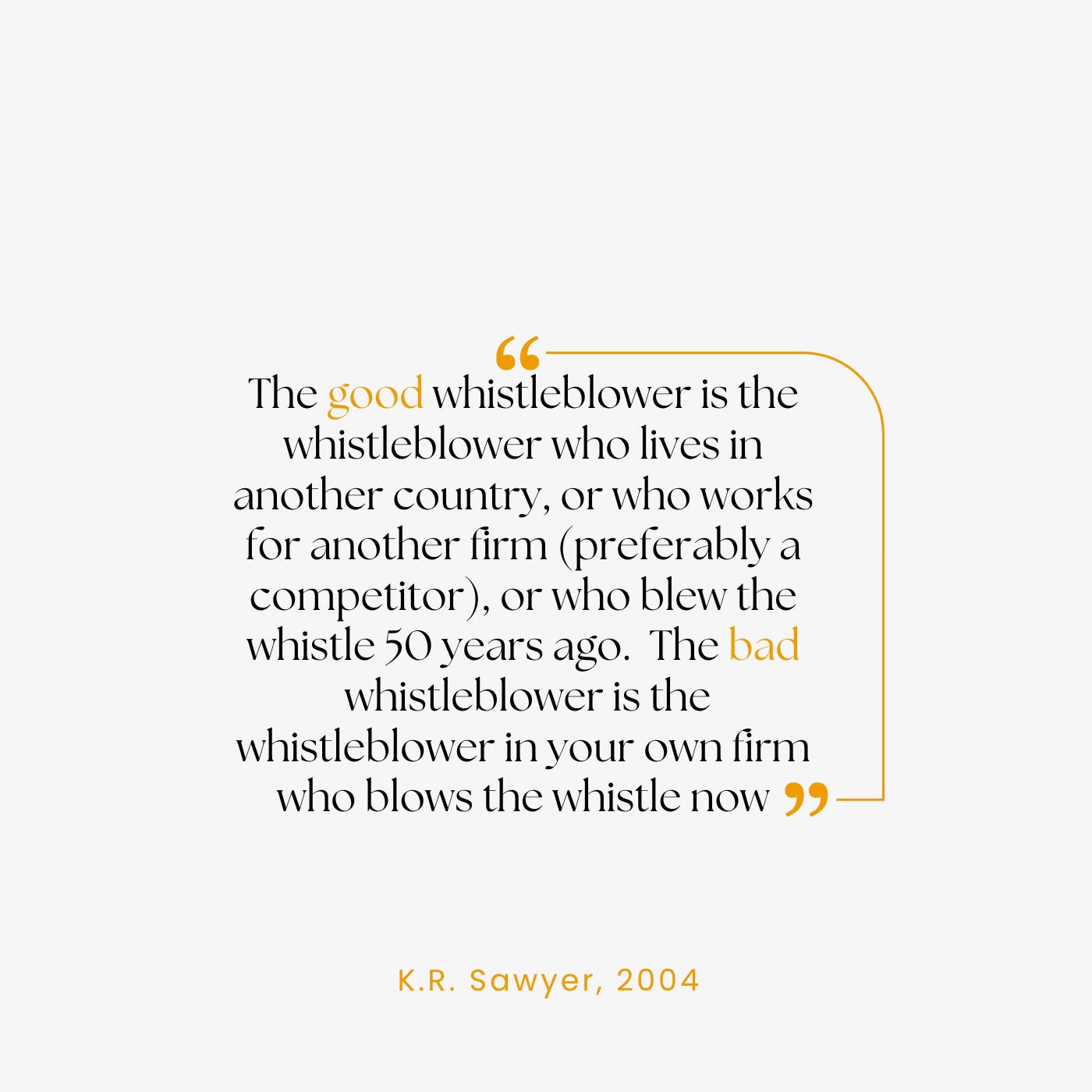

There's very mixed research on the extent to which people suffer after whistleblowing and speaking up. Some researchers have commented that it's a "significant minority" but emphasise it is a minority. Our feeling is that if people speak up and talk truth and don't face recriminations, that's just part of doing your job. I think most people that we've talked to who've spoken up, feel like recrimination is an essential part of the experience of whistleblowing and "speaking up".

Some people did predict that there was going to be conflict about what they were talking about, they recognised that what they were raising would not be appreciated. But for many people they just saw it as being what was expected of them in their role. And so this workshop obviously is offered for people who have experienced recrimination. And if you spoke about wrongdoing and didn't face that, then great. But I think it's unlikely that the idea of this workshop would have resonated with you. I think things become very difficult when, not only do you have to brace yourself for telling the inconvenient truth, but you have to cope with the recrimination and punishment that follows afterwards.

It's clear to us, not only from our experience (not just our personal experience but also having worked with many people), and also in our reading of the research literature, that whistleblowing and speaking up has the ability to not only profoundly harm the person but also to have a destructive effect on their entire life thereafter. And there's actually very little specialist support available. Some people may have accessed employee assistance counselling. But for many people, it was quite hard to engage with that in a constructive way because of the association with work, no matter how sympathetic the counsellor was. Also the availability of support is often very limited in time within the organization for instance, 6 sessions. And for many people, the effects of speaking up go on long after their association with the organisation has ended. It’s evident that people are struggling with the trauma of speaking up months or even years after their association with the organisation has ended. They find that they're still having a reaction or are very emotionally activated by what's happened to them despite the amount of time that has lapsed.

So we're going to describe the processes at work and we'll focus less on the tactics used by organisations, which you have very little control over, and focus more on outlining how our own vulnerabilities can become complicit in the process and contribute to us getting stuck. Then we'll move on to strategies for healing.

How does recrimination affect the physical health of those who speak up?

Des McVey [00:07:13]:

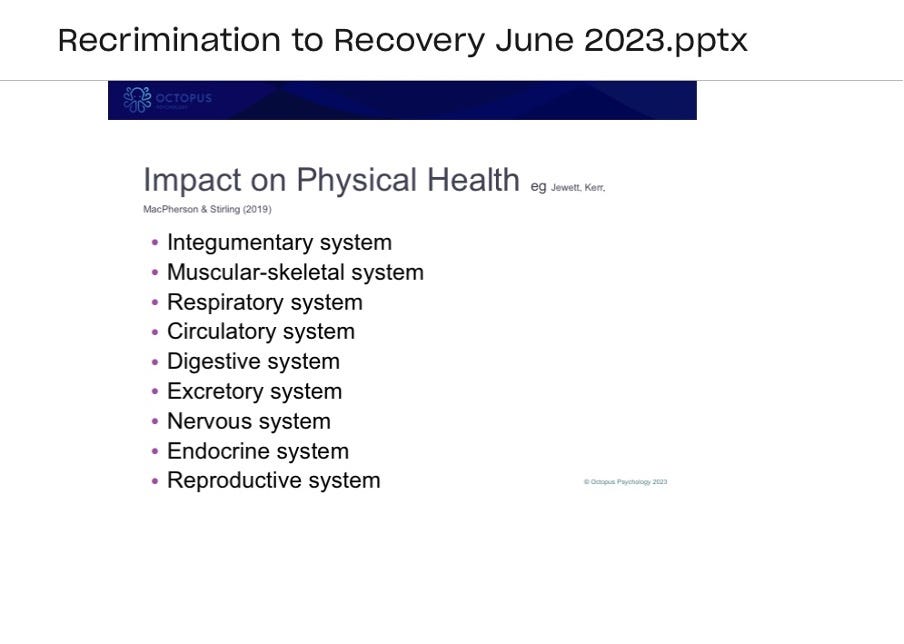

In terms of trauma, both in general and in trauma during recrimination, it has a massive impact on your physical health. It's becoming more commonplace to correlate physical health with the mind and particularly how trauma can manifest itself through the body and can be remembered within the body. I do remember working with several patients who were significantly traumatised and their trauma was replayed via their body.

One man I worked with suffered extensive violence in his childhood. And during the process of talking through his experiences, he woke up one morning with black eyes. Another man was abused horrifically in a children's home and when he talked about the process, he woke up during the night bleeding from his anus. So you can't underestimate the power of the body to remember, to store and to hold the trauma.

Our bodies are used to functioning with the reptilian part of the brain activating in response to cues of danger – it triggers the fight-flight-freeze-collapse response to threat but it's only generally intended as a short term response until you find shelter or safety. The difficulty with whistleblowing, and being in a state of recrimination, is that this threat activation system is continually active at some level for a lengthy period and that has a massive impact on the major systems of the body.

It impacts on your ability to fight infection. We know that the constant release of cortisol impacts on the bones and the skeletal structure and in some cases can lead to rheumatoid arthritis. The respiratory system is also massively impacted and sometimes a person's pulse rate is up as high as 175 even when the person is not actually confronting the dynamic.

85% of serotonin - the feel good chemical - is produced in the gut. Consequently, the gut is often referred to as the ‘second brain’ and there can be lots of difficulties when you experience trauma which are manifest through the gut such as IBS. When the pulse rate is highly elevated, the body goes into a mode where it wants to excrete all the waste products. So, it's not uncommon for people to experience serious effects such as diarrhoea, constipation, et cetera.

The endocrine system is impacted because the autonomic nervous system is on alert all the time and we've spoken with some people who have experienced the development of diabetes, are having thyroid problems and again becoming really tired really quickly. The reproductive system has also been impacted for them because stress obviously impacts on your sexual drive and this cam also affect your sexually intimate relationships. So what we notice with people who have whistleblown is their body is constantly under attack and this can last for sometimes up to as long as ten years as you go through the process.

Naomi Murphy [00:10:26]:

It's probably also worth adding that we know from studies of intergenerational trauma, and the impact that trauma has on your body, that we can also pass on our trauma through our DNA and this can be activated in future offspring. So not only do problems such as stress impact some people's fertility, but also it can affect any future children that are born. I think the other thing to emphasise is about how much our physical health interacts with other areas of our life. Studies suggest that 70% of people who've spoken up experience stress related physical symptoms. And if you're in an occupation like sports, if you make a living out of performing elite sports, then obviously that's going to impact on whether you acquire injuries, your stamina, and as well as your ability to cope with other life events.

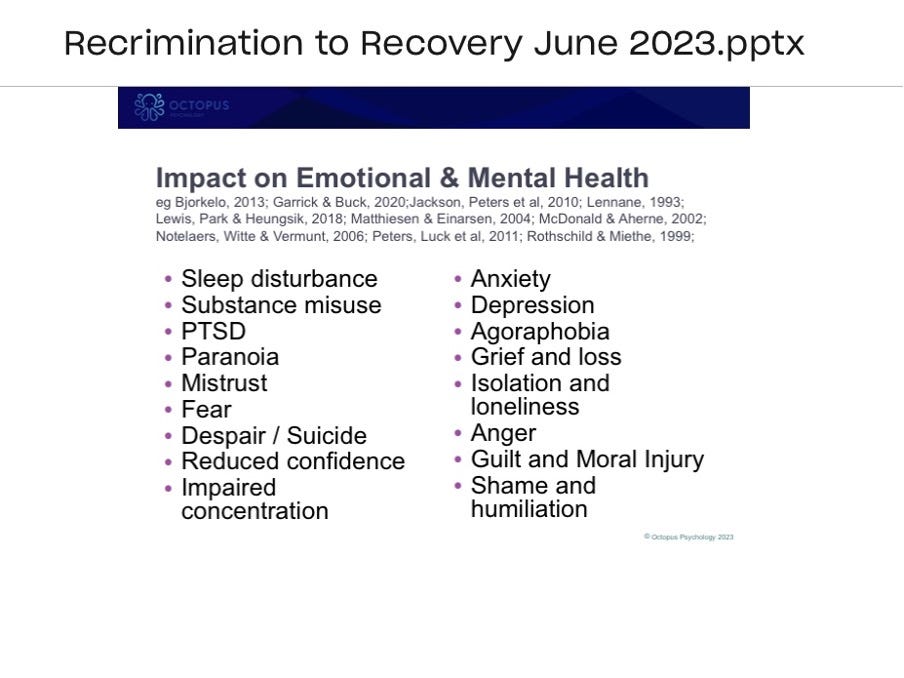

So in terms of the impact on our emotional and mental health, we've listed some of the studies on the slides, but there's so much research on how much our emotional and mental health is affected and we know that recrimination can have a really devastating effect.

What’s the impact on mental and emotional health?

One study by Van der Velden et al recorded that 85% whistleblowers experienced symptoms like anxiety, depression, paranoia, agoraphobia or sleep issues. And in that same study, 48% experienced symptoms to such a degree that they could have been formally diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And what was really interesting about that study is they matched whistleblowers with other working adults and also with people with a diagnosis of cancer and found that those who spoke up and whistleblew had the worst outcomes of the three groups .

But there are other emotions that we know are associated with poor mental health but wouldn't necessarily warrant a diagnosis. You wouldn't get a diagnosis necessarily if you experience extreme shame for example. But I think shame is one of the really overriding emotions that people experience. I know myself when I've experienced recrimination for speaking up, I was used to being somebody who performed well, was seen as performing well, and given a lot of responsibility as a result. But then I was subjected to malicious allegations and treated in a way that was very shaming. And it makes you feel quite humiliated.

Shame is implicated in lots of conditions like anxiety and depression, but we don't diagnose chronic shame in itself. Similarly, anger. People are left feeling very angry and very resentful. And people often want to not only get justice, but sometimes there's a sense of wanting revenge against those who've harmed them and hurt them. And that's really understandable. But there's a really fantastic phrase about how "Resentment is like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die" (St Augustine). Ultimately, if we're caught up in feeling angry, we are the people that end up swallowing that down. And for many whistleblowers, their experience of speaking up ends up dominating their whole lives. So they're preoccupied with it. It impacts on all areas. Whereas the people that they're angry with, the people they feel victimized by, for them it's just part of what they're doing during the course of their working week. It doesn't take on the same scale within the organisation.

Also I’d like to mention the role of guilt and moral injury. Many whistleblowers are motivated by the desire to avoid moral injury, that sense of guilt at being complicit in wrongdoing. And for many people they give that as the motivation for speaking up, for challenging their organisation's authority. But when speaking up doesn't prevent further or future harm, then it can be hard for the whistleblower, the person speaking up, to shake that off. Speaking up might also negatively impact on your colleagues. If you're a whistleblower in sport who's spoken up first instance and you then find that your team has been affected. Or your sport has lost funding as a consequence of you speaking up. So there's a huge burden that people carry after speaking up. Even if the person speaking up has done everything that they can and acted with integrity as a person.

Des McVey [00:15:10]:

I don't think we can underestimate the role that shame can play with people who speak up. It can be a huge factor in them becoming isolated and retreating from others. And sadly, at times the shame, along with the anger, has often resulted in people killing themselves because they can't tolerate the toxic emotion of shame. It's just such an understudied emotion in all sort of areas of mental health.

Naomi Murphy [00:15:35]:

And also grief and loss. I think for many people who speak up, they've always prided themselves on doing a good job. They've often been people who've won medals or awards, won accolades. Their performance reviews have often referred to their “exceptional performance” and they're often been very committed and very passionate about the work that they've been doing. And then they find themselves demoted or marginalised, possibly sacked or made redundant, feeling like they have to go and work in a different area, get a new job. And so there's a huge sense of loss. And Alford talks about a number of losses but primarily that loss being the loss of your truth. Say, for example, the loss of the idea that justice can be relied on.

For me personally, I suppose I was living with the belief that somehow an organisation would know what was the right thing to do and somebody at some level would care. And actually when you speak up sometimes you find that that isn't the case. And that can be really quite a shocking, profound loss though it might on the face of it seem to be very obvious. Other people might say why would you have that belief in the organisation's health anyway? But for each of us, we carry beliefs about the world and the process of speaking up means that that can be challenged. And sometimes we have to let go. Let go of our identity, let go of our beliefs and let go of what our truth is. And sadly for people who speak up that doesn't end when the situation ends. You don't leave that situation and everything's automatically okay. The harm that's caused to our physical health, to our emotional and mental health that continues for many people, in many cases, after the end of the association with the organisation.

So the other areas of life that can be affected are - obviously in work. We might find that we have a loss of purpose, a loss of motivation. If you're chronically stressed, it's really hard to concentrate, it's really hard to focus, it's really hard to learn. I've already mentioned about the possibility of loss of funding in sport. Maybe you're impacting not only on your team but also on your whole sport?

It affects our time. When people speak up, they become really all-consumed by the experience. And we hear from very many people how often organisations misuse process. People stay there believing the organisation is following a particular process and that you will reach the next stage within a month or two months. But then before you know it, six months has past and at some level, there's perhaps reliance on exhausting your ability or your will to go on with that process.

There's also potential for a huge impact on your finances. Some people end up losing their jobs or find themselves demoted. Other people start engaging in legal processes which also have the potential to significantly impact on how much money is available, which of course then can add further strain and stress to the household and impact on your relationship.

As Des already mentioned, it can impact on your libido which potentially then puts distance between you and a partner. It impacts on your patience, your irritability and people can become quite preoccupied with the idea of getting justice which can become quite boring or irritating to those around them. And sometimes people who speak up find themselves feeling really quite alienated from their friends and from loved ones because they have a sense that actually maybe their friends wouldn't act the way that they acted. And some of your friends might think you should just drop it, you should just move on when it can feel quite hard to do that.

Des McVey [00:19:59]:

They accept or understand that you're constantly functioning at best in midbrain and of course when you're in midbrain you're totally tunnel visioned trying to save yourself if you like. So there's a massive impact on your memory as well and you can forget things, forget to do things and I think sometimes your loved ones and friends see how much pain you're in trying to encourage you to let it go. So it comes from a good place but for the whistleblower, because they're stuck in that tunnel focus they need a better and more healthier resolution and the ability to walk away is sometimes just not there.

Naomi Murphy [00:20:41]:

We mentioned identity and reputation. Obviously for many people, work takes up a big part of how we spend our adult life. We spend alot of our adult life engaged in work, don't we? To some degree we define ourselves by who we are, by what we do, not just who we are in our personal lives. And so to actually have that questioned or challenged in some way, to have that threatened to be removed from us, our reputation damaged is extremely painful. As I said, many people who speak up and then find themselves denigrated are people who've previously been very well regarded within their profession. So it's an awful lot of loss. And all these things obviously can interact with one another because I think there's only so much that people can juggle at any one point in time.

How are people harmed?

Naomi Murphy [00:21:37]:

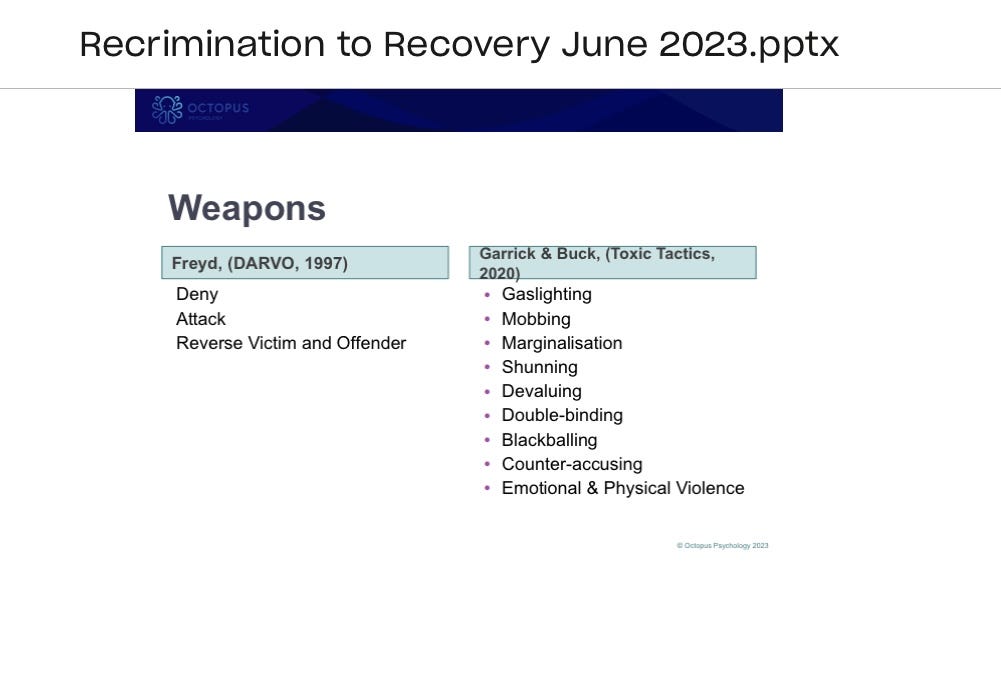

In terms of what processes are at work, there's some excellent work being done on the processes that organisations use as weapons against those who speak up in order to silence, discredit and punish them. And we're going to touch briefly on these, but many of these… we're referring to them as weapons because actually the whistleblower, the person speaking up, has very little power to control what happens. You might be able to expose yourself to them a little less, but you'll probably find it hard to outdo them. I think for many people who speak up, they do have the idea that David is going to somehow outwit Goliath and that's very difficult when the organisation that you may have taken on may have an awful lot of weapons which they can use against you.

The first theory that I'd like to draw on is Jennifer Freyd. She's a clinical psychologist and during childhood she was sexually abused by her father. And when she disclosed this in adulthood, her father insisted that the memories had been implanted in her by a therapist who'd induced false memory and he set up the False Memory Society. And Freyd talks about betrayal trauma, the idea that there's a particular traumatic experience of being let down by the people who should have looked after you and protected you.

And you can see the parallels in the workplace. In that, in work there is an expectation that work has a responsibility to keep you safe. That's why we have Health and Safety legislation. And when that doesn't happen, we do experience this profound sense of betrayal. But also, Freyd introduced the idea of DARVO that when people speak up and point out wrongdoing, what often happens is the perpetrator firstly denies the allegations in the first place and then sets about attacking the person who has voiced the harms and so reverses the role of victim and offender. And that's very much something that you can see within the work on whistleblowing.

Moving on, there’s a really great paper by Garrick and Buck where they outline nine toxic tactics that organisations use against people who speak up. I'm not going to dwell loads on these because I think people are probably quite familiar with them unfortunately. So the idea of gaslighting - that is denying and minimizing the experience of the whistleblower and the person who's spoken up. And reflecting back over my career, when I've spoken up, there been times where you're made to think, “Am I making a mountain out of a molehill here? Have I exaggerated or embellished this in some way?” I've spoken to lots of other people who've had that same kind of experience. And it does seem to be that that's an organisational response to speaking up is to somehow deny or minimise it, make it sound like it's no big deal.

There's the notion of “mobbing” - pressurising other employees to inform or collude with their perspective on the person who's spoken up. So ultimately, your work colleagues could end up also feeling like, well, you're making a big song and dance out of something that's not so significant.

The person who speaks up is often physically isolated and publicly shamed in a process of marginalisation. And that might be literally moving you to another part of the organisation, making you go and work somewhere away from the work colleagues that you've worked with, giving you tasks that are perhaps not the work that you would ordinarily be working on, and perhaps encouraging you to be ostracised and removed from emotionally supportive colleagues via shunning. And sometimes people who speak up are complicit with that themselves because of that sense of profound shame at what's happened and this awful fear of "are people going to believe what's being said about you?" Then it's very easy to withdraw and isolate yourself and move away from people that might be able to offer support.

But equally, I think people who speak up are often quite shocked by the inability of their colleagues to speak up and support them, because actually, the more people who speak up, there's greater safety in numbers, right? So actually, if other people stay silent, it leaves the whistleblower, the person who's spoken up, out on a limb on their own. And that can be really difficult to cope with in terms of the devaluing whistleblowers. People who speak up often talk about being given tasks which are menial relative to their position or status within the organization. People might find themselves moved on, their post is made redundant and they're offered posts in other parts of that NHS Trust for example that are at a lower grade and whilst their salary would be protected for a couple of years, they would then lose that. And there's something devaluing in placing somebody in a position where they perhaps have lots of seniority and that's not being valued or appreciated.

People who speak up often have a sense of being blackballed. So the idea that word is being spread, that "you’re trouble", which makes it hard to get other jobs afterwards. And a common feeling from people who've spoken up is that sense of they won't be able to work in their field again. The view of whistleblowers and people who speak up is so polarising. People have the idea that either they're ‘heroes’ doing something that's really great or they're 'snitches' who've shown no loyalty to their company, to their team, to their profession. So that can be very difficult to cope with.

And then there are counter accusations. People find themselves the subject of malicious allegations, being accused of doing all sorts of acts of wrongdoing and for people who have acted from a place of integrity (and all the research seems to suggest that that is the main motivation of people who speak up) the idea that people who speak up are 'disgruntled malicious individuals just seeking vengeance for petty grievances of their own' doesn't seem to be borne out in the research at all, as I'm sure most people here know. So you're a person of integrity who's acted in a very community spirited focus, you've stuck your neck on the line, you've raised your head above the parapet to highlight some wrongdoing within the organisation and then find yourself being accused of something awful yourself. And people often find themselves feeling as if they've been tarred and feathered, so this is public humiliation.

And finally, some people even report experiencing emotional and physical violence. I remember going to work in a prison many years ago and someone saying to me don't ever make any enemies working here because you'll come back and find your tyre slashed in the car park. I was in my twenties and horrified that this was an organisation that was supposed to be upholding the law and yet for some reason that it seemed perfectly legitimate for people to enact revenge if you were to highlight something that was negative. And Garrick and Buck highlight quite significant levels of fear amongst the people in their study. I think that about 65% of their sample said that they felt either very significantly or very frightened and that 14% of the sample had actually been physically or sexually assaulted. Also we hear stories of athletes having to hide in other countries because they feared for their physical safety. And whilst we might like to think that's only in countries like Russia that we need to put some kind of distance between us and the organisation we’ve spoken up about, there's enough stories of whistleblowers who’ve died in suspicious circumstances within the UK. Obviously, there are people like David Kelly. There are enough people like that who've died in suspicious circumstances to give this sense of "my life could be at risk by speaking up now". And it's not only the individual themselves that might be threatened, but often people have felt frightened for the safety of their family.

Do you have any control over the strategies used to silence you?

So these three items here are ways in which the person speaking up does have some control. Often people might be tempted to go down the line of seeking an employment tribunal, hoping for justice and thinking “There'll be a due process that will somehow work out right and things will be straightforward, the truth will be outed and I will be vindicated”. And sadly, I was talking to somebody from Justice for Whistleblowers who told me that less than 5%, maybe as little as 3% of people who go to employment tribunals after speaking up actually win their cases. And even when people win their cases, they don't necessarily get the vindication and justice or satisfaction from that process. People are let down by the process.

In terms of mental health, I think for many people who speak up, they find that they are encouraged to access mental health services. Now there's something about recognising that you’re under a lot of strain and wanting to access emotional support might be a good thing. But sometimes the person speaking up engages with that in a way where they want to prove how much the organisation is harming them and hurting them by not listening to them, not taking them seriously by using toxic tactics. And so actually at times they present the organisation with information that then will be weaponised and used against them. So there is research that's found that organisations will make use of the person who's spoken up; if they've been in contact with mental health services they'll make use of that.

And I think also there's time. There's something about how long does the person who's speaking up engage with this process? So often the organisations themselves might want to just get shot of you, get rid of you as quickly as possible. And there is something about finding a way to do that in a way that gives the person who's spoken up as much of their credibility and power back as they feel they can manage to get. But often people are holding out hope for something that's probably not going to be forthcoming. And so I think all individuals need to make an effective risk assessment decision about what are going to be the demands for them in engaging with some of these processes and consider whether they appeal against grievance proceedings. There comes a point where you have to think "do I need to draw the line here or do I move on?"

How does recrimination interact with your own history?

Des McVey [00:34:21]:

In talking to other people and from our own stories, we see two different ways the trauma is experienced and manifest when you're stuck in the recrimination process. And I'm sure that none of us present today have escaped our childhood without experiencing difficult times on occasions. Some of us here today, myself included, have experienced a significant trauma in childhood that has impacted on our belief system and how we believe that the world will look after us, whether institutions will look after us, whether people charged with our care will look after us. So we kind of operate with a strategy that we won't be looked after. Personally my own strategy was to be outspoken and forthright and that seemed to protect me as I went along and it does keep you safe but when you're exposed to the toxic attacks you realise that your strategies aren't working and rather than becoming traumatised you experience a re-traumatisation. You're back into that dynamic you were in as a child where you're powerless, where you can't use your strategies. The strategies you developed aren't working anymore. So you get into a state of retraumatization. And personally for me it was very much about being powerless and not having the strategies that I used.

For those not unfortunate enough to be abused, this is a new trauma, entirely new trauma and I think a salient issues around that is betrayal. Betrayal of trust and lack of confidence. But certainly both dynamics permeate through several specific areas including your identity and your personality importantly. And we try to manage these while we're working through a psychic trauma and a crisis. So to summarise that, we think that there's two different ways the re crimination is experienced depending on history. There's those who are being traumatised for the first time and those experiencing re-traumatisation. Your view of the world is challenged, your view of your relationships is challenged. Your view of your safety is challenged.

In those who have already experienced a trauma, they are re-traumatised and their view of the world is confirmed. That view that you held either consciously or subconsciously has come to the forefront and it's reconfirmed once again. And so for the re-traumatised individual a lot of work possibly has to be done with the core trauma whereas with the newly traumatised individual, it's working directly with what's going on with them in the present moment.

Naomi Murphy [00:37:14]:

I would probably chip in there that I was lucky enough that I felt pretty safe during childhood. I probably also would have been seen as a bit of a 'goodie two shoes' at school. Often the teacher's pet, the favourite in work, often given tasks and duties probably beyond the level and grade that I was at because I was trusted and it was felt like I could do a good job of that. And so I was used to people expecting me to do well and finding it fairly straightforward and fairly easy. And every time I've spoken up, and obviously I'm a slow learner because every time I've spoken up, I've had this shock of I'm being treated like I'm the person who's a troublemaker, who's guilty of some kind of wrongdoing. And for me that was traumatising because it meant I was being seen in a way that I hadn't previously had that experience of. And having to cope with the shame of being seen as a troublemaker was really quite profoundly disturbing to me.

Des McVey [00:38:26]:

In one organisation I was referred to with anger by a senior manager as "the self appointed moral conscious of the organisation". But at least at that stage in my career I was safe. People knew I was outspoken and I felt protected by that. So my strategy was working. It was more recently when it was over-ridden and I felt totally powerless and re-traumatised.

What’s the process?

Des McVey [00:39:11]:

You have emotions and you identify with emotions like sadness, fear, shame. When we talk about affect, we are talking about the whole experience. It's how your body reacts to the emotion, how your cognitions work with the emotion. So in short, we all develop our personalities to help us manage our interpersonal relationships and keep us safe. So for example, if we return something back to a shop, we use our personality and say "This thing's broken, I've got my receipt and I want an exchange please". If the person just ignored you and says "Nah, it's not happening", you assert your personality all the more and say "okay, I've got the receipt, I know my rights, can I have an exchange?" And then they say "No" and give you the impression that they're not listening to you. At some point you become highly anxious because your personality is not working, it's not managing your affect and you can actually become very chaotic or irate.

So when faced with the toxic tactics in the workplace, your experience can be that your personality is not working. Your personality may have been to be forthright and outspoken. It has just been centred on working hard and being conscientious and a hard worker that's trusted as well. So what you are now left doing is scrambling around to find a personality strategy to use. I think perhaps that the best example to exemplify it is that it's like you're in a constant state of 'road rage'. If you're in your car and you're in a competition with another vehicle, you don't have your personality to negotiate the situation. And that creates road rage. The dynamic that creates road rage is the inability to use your personality to negotiate the situation. People who speak out are in constant state of 'road rage' because whatever they try to do with their personality, it's not working. And I suppose you scramble around to try and find a personality strategy to help you get through, which I suppose in the terms of Schema Therapy it's often referred to as schema modes. And you could end up being in a punitive parent mode and you constantly feel that someone has to be blamed, there has to be punishment and accountability somewhere and the only resolution is to blame someone. And that can be internally and externally manifested.

Or you could adopt what is referred to as an 'enraged child' personality which manifests itself as "I've been treated unfairly, I'm not going to cooperate and I have strong negative behaviours and am hoping for some sort of catastrophe to happen". So you find you can find yourself wishing something really serious would happen to validate what you've reported and what's going on. It becomes very chaotic.

Or you could adopt a 'bully-attack mode' that is humiliating and challenging and you tend to go for working in a machiavellian way. And certainly I think that was my strategy. And strategies for people who are re-traumatised, who have already experienced negative hostility from people in power tend to use a bully attack mode and try and orchestrate their way to attack and be machiavellian in this strategy.

I think for people where it's their first really significant trauma, they are at risk of going into a vulnerable child mode and becoming withdrawn. There's a lot of shame, loneliness, anxiety and they kind of collapse, sleeping a lot and just sadly soaking up the trauma. So I think people will adopt different maladaptive personality strategies in order to try and get through depending on whether they've been traumatised or re-traumatised during the process.

Naomi Murphy [00:43:17]:

I think that what we've happened across quite commonly in people who've spoken up is firstly this idea of how easy it is to fall into embracing victimisation. So people have been victimised but actually they don't have to embrace being a victim going forward. The injustice of the situation can almost make some people hold on to and cling on to this sense that they've been victimised by the organisation. And I know that's about trying to get validation for how awfully you've been treated, but ultimately it keeps you in a position that makes it very difficult to move on and move forward to have a better outcome for yourself. And I think the other pattern that is often engaged in by people who've spoken up is the idea of 'moral narcissism'. So I think people who speak up rightly should feel proud for having the courage to speak up. I think there's an idea that it comes easy to people who've spoken up, but that's not my experience of people. I think often people have had a sense that there was going to be trouble ahead or conflict. They haven't wanted to have those difficult conversations. They've known that they're going to be unpopular or the truth isn't going to be welcomed, but they've dug deep and they've done that despite knowing that. So pride is definitely something that should be drawn on for a healthy part of the identity going forward. But I think sometimes people can get stuck in moral narcissism and a way of looking at the world from a position of superiority to try and level the playing field again. But the problem with moral narcissism is it pushes other people away and actually can make other people feel the same sense of defectiveness and inadequacy that the person who's spoken up might be feeling because of how they've been treated. So it's not necessarily the most helpful position to be in, even if it's a phase that people might need to go through in the shorter term.

Des McVey [00:45:35]:

I think in terms of the coping strategies that you adopt, some people can stick to just one strategy, other people may flip between different strategies in order to try and cope and you're effectively trying to find a way to manage your affect and engage with the other person. But as I say, it's like being in road rage. The other car driver is not interested in you, you're stuck trying to find a way out. And sadly, some people, including myself, you find that there's parts of you that you don't like that come to the forefront because of your anger and your fear and you can have intrusive thoughts that just aren't helpful at all.

Naomi Murphy [00:46:20]:

As Des has said already, when people are traumatised, they're stuck in this fight-flight situation for often months or even years in some people's cases. Or people deteriorate further into collapse, freeze and collapse with the hopelessness of the situation. The idea that they tried everything that they can to somehow get the justice, to somehow get somebody to recognise and acknowledge their truth and the wrongdoing that they're trying to draw attention to. And our bodies just are not made for coping with stress over that kind of period. And that's why we see these impacts on all of our bodily systems but also end up with people having really quite severe difficulties in coping in an emotional way or find then it's impacting on their concentration and focus and their ability to think and make decisions.

Des McVey [00:47:26]:

Finally, you use these strategies both to make sense and judge other people, but you use them internally as well. And you can be very punitive towards yourself. Blaming yourself for being stupid, blaming yourself for not being strong enough. It is both internalised and externalised and therefore becomes very self perpetuating and I strongly believe that you can end up stuck in this vicious psychic trauma.

A pathway to recovery

Naomi Murphy [00:47:58]:

In terms of treatment, as a psychologist or a psychological therapist, when we're thinking about helping people move on out of a period of crisis, and I think if you've suffered recrimination and you're still experiencing emotional distress and the physical consequences of speaking up and being recriminated against, then there's a degree of crisis present.

And as therapists, psychologists working with people in this kind of state, the first port of call from a therapeutic point of view is to try and help the person be less emotionally aroused and create a sense of safety. Because if you're flooded with anxiety, you can't learn, you can't grow. It's not possible to engage with the world in the way that you need to.

And I suppose the first question to be asking is "are you actively under threat right now or are you keeping yourself in some kind of fight?" and being honest with yourself about whether there's a possibility of bringing that fight to a close and thinking about what you'd have to give up to do that. So a lot of the things on this list are common sense. We know them and they're easier said than done. But I think we stop thinking about them when we hit a crisis. And I know myself when I've been in a position of speaking up and really felt quite powerless, I haven't necessarily automatically done these things. As a psychologist, I've been used to coaching other people in taking these kind of actions. I had to give myself a good talking to about trying to do some of the things that I know are good for our emotional, physical and mental health.

So firstly, about maximising safety. As human beings, our biggest and fastest route to safety is by connecting with people that we know are safe, our loved ones, people who we turn to for comfort during times of distress and sometimes during the process of speaking up, people have retreated or withdrawn a little from loved ones. So there's something about reconnecting and building those bridges and repairing them if they've been become a little bit fractured.

I think for a lot of people they get real benefit out of connecting with other people who've spoken up. There's a real sense of solace. I know myself when experiencing the sense of shame about speaking up that somebody who I didn't know very well rang me and shared a very similar experience with me. And there was something really freeing about that. I felt I was seen by that person and the person validated and understood my experience. And it also helped me realise that I wasn't necessarily going to be judged the way that I feared that I was going to be judged.

And in fact, it actually also started making me aware to how common these kind of experiences are. So I think actually it can be really helpful to engage with the support of those organizations that are there. I think we've got Justice for Whistleblowers here, Whistleblower Network, there are various different organisations who do their best to provide support and comfort, but also advice and guidance to people who've spoken up. And I think that can be really, really helpful to engage with people.

But actually the other element of engaging with whistleblowing communities is that sometimes we can end up being stuck in this routine of engaging with other people that are stuck in that same process. And we might find ourselves re-activated or feeling re-traumatised by hearing other people's experiences that really resonate with our own experience. And I know for me, when I was thinking about working with people who'd been involved in speaking up, when I was first thinking about offering something to people, my concern was can I do this right now? Is this going to activate me given experiences that I've had over my working career but in fact found that I have been able to move on and develop a new chapter to my story. So there's something about getting the balance of connection, but actually knowing when it's possible to and when it's important to pull away from other people who've had very similar experiences.

Then there's something about reestablishing our routine. I think routines very easily go out the window, especially if you've found yourself with more time on your hands. Maybe you've been suspended or had to leave your job and haven't found a new job to go to. So the idea that we get up, we get ready, we go to work and we do that maybe five days a week. For some people, that routine disappears. So it's important to try and keep some kind of routine, getting up at a reasonable time in the morning, going to bed at a reasonable time, making sure that there's purposeful activity during the course of the day, making sure we replenish ourselves with good food and hydrate ourselves with water.

And Des spoke earlier about the role that our gut plays in mental health and the fact that we know that 'feel good' neurotransmitters. So serotonin is very present in our stomach. Well, if we're feeding our bodies junk food, alcohol, illicit drugs, obviously we're going to be upsetting the balance within our bodies. And there's something about trying not to introduce new stimuli into the body, trying to help your body be at its best and giving it its best shot at health. And it's hard to do that if you're eating lots of sugary food to cope with all the strain that's there for your body. So we don't want to be ingesting toxins where that's possible. Like I say, I know I'm making it sound really simple and straightforward and it isn't the case. But there is something about being mindful and actually, if you don't have routine, maybe making your own physical and emotional well being the project that you're working on, that's really important.

I think for many people who speak up, they have a history of prioritising other people's needs over their own. That's often been a factor in why they've spoken up in the first place. They prioritise the well being of the community over their own physical integrity, their own survival. And so actually shifting the balance and prioritising yourself and focusing attention on getting yourself fit and healthy doesn't necessarily spring easily to mind.

We know the importance of movement for health and I think really here the emphasis is on stretching and strength rather than cardiovascular stuff. So for some people, cardiovascular exercise can amplify and exacerbate that sense of fight and flight. So it creates a sense of agitation that's difficult to deal with. But I don't want to be prescriptive. For some people, they find that actually they really burn off energy by engaging in cardiovascular work. They don't feel good if they're not able to engage in those sorts of things. But obviously the more that you're engaging in movement, the more important it is to be trying to counteract the stress that you experience. And because you don't want to be incurring physical injuries because your body and your structure is holding lots of strain and stress within the body.

Which brings us to nasal breathing. When we're stressed, we have a tendency to take large gulps of air through our mouth. What that does is activates our lungs, activates our heart rates, raises our heart rate, and it keeps all our breathing in the top half of our body and can put our bodies in situations that are close to a sense of panic. The most adaptive way for breathing..... And I know that people might be sat here thinking, "good heavens, she's telling me how to breathe". But actually nasal breathing is associated with much better health. So when we breathe through our nose, the breath goes deep down into our stomach which helps with the neurotransmitters. Again, when we breathe through our nose we release nitrous oxide and that's the only way we release the nitrous oxide. When we breathe through our mouth we don't get that and we need nitrous oxide to help our bodies be in a state of health and well being. And of course I think for many of us as psychologists that might be present because I know there's quite a few here, people are involved in teaching and education, people who do presentations. We end up in the bad habit of breathing through our mouths because that's what we're doing as we're talking. We don't have the time. So there's something about kind of like trying to practice the nasal breathing and doing that as much as we can do when we're not actually actively having to talk.

It's important to raise our interceptive awareness. And what do I mean by that? Interception is our ability to detect and sense what's going on inside our bodies. So if you're feeling anxious well, how are you detecting the anxiety in your body? Is your stomach jittery and full of butterflies? Are you having a sense of wanting to move around and is your leg tapping? Or if you're feeling happy, how do you notice that you're feeling happy? How do you notice when you're feeling frightened? Just really trying to turn attention inwards and noticing what's going on inside can be really crucial because that can help you recognise the first signs of stress so that you can start trying to calm yourself down and implement strategies that, you know, make you feel safer.

And also making use of natural resources. So we know that lights, we know that green space, getting out into nature, blue space, the awe of the sea, animals, things like touching wood, all of these things are really well researched and we know that they have a calming effect on our nervous systems. So none of these tactics in itself is probably going to make a massive shift in how you might be feeling. But actually if you are able to put together some of these strategies and focus on the ones that have most resonance for you and that feel easier to engage with, then what you're doing is giving your body the best chance it can to replenish.

Sleep obviously can be easier said than done. Many people who speak up find that they're experiencing nightmares might have problems getting off to sleep, find it difficult, find it difficult to stay asleep. But I think keeping a routine that's as close as to a normal sleep routine exploring good sleep hygiene, not lying in bed for hours, tossing and turning but getting up and doing something and then going back to bed. The obvious things about not using blue light close to bedtime and sometimes people find that they can make use of calming technology. So people probably heard of devices likeMuse, which is a headset that's used to help people meditate. Apollo Neuro uses vibrations to stimulate your vagus nerve and can be used to help you get into a state of calm you, or to help you go to sleep. RoshiWave are glasses that use light stimulation to calm you and get you back into a state of regulation. And NeurOptimal, is a form of bio-neurofeedback that doesn't need someone else to administer.

Making a transition out of recrimination into recovery

So one of the themes that really comes up in talking to people who've spoken up is the idea of transitions. And there’s some really great work by Bruce Feiler on this and his book's really readable and very accessible, and I'd encourage people to read it. I personally found it really useful to reflect on when in a position of feeling a bit at sea with what had happened to me. And there is a theory that depression is intended as a message to tell us that something isn't working and we need to do something different. And the kind of crisis that comes after recrimination forces us into a transition. And I think these three quotes from Feiler are really quite key:

So transition is a moment when you're forced to evaluate who you are. And I think this is what happens after speaking up. People have this profound experience of needing to make sense of who they are, how they relate to others, and how they relate to their work, their organisation, and how to make sense of that.

Feiler also talks about transitions being "a lifetime sport, that no one is teaching us how to play". And he suggests that typically over the course of our life, we experience three to five major transitions. And each of those transitions could take between three to five years to fully come through and resolve. And he identifies the five key causes of disruption that cause transitions, and these are love and the kind of relationship we might find ourselves in or without, our identity, our beliefs, our work and our body. And I think you can kind of tell that many of those are in some way connected to the experience of speaking up and the recrimination that might follow.

He also highlights how we have to shed parts of our personality and our identity to make space for new parts and to go forward. And I think one of the things that's really striking talking to people who've spoken up and who felt stuck is that they're often stuck in this story where there is no way forward, there isn't a next chapter emerging naturally. And Alford talks about that. She talks about how people who've whistleblown or spoken up can end up having a chronology rather than a story. So they have a timeline of events that have happened rather than being able to make sense of it and integrate it and create a new story. So in terms of mastering the transition, what's needed in mastering the transition involves some degree of acceptance, a degree of self compassion and also the ability to let go.

There's something about accepting that you're in a transition and having to be willing to let go of part of your life which can feel very difficult. It can feel frightening and threatening and unwanted. It's not something that people have chosen for themselves.

Is there more to learn?

People have found themselves thrust into this position of transition. But I think there's a really good metaphor about driving a car. That actually if you're driving a car as Des introduce the idea of driving earlier. But if you're constantly looking in the rear view mirror and looking at the road behind you, then what's going to happen on the road ahead of you? And are you going to find yourself in another collision? Looking behind you implies that there's more to be learned from the scene. Would you have done things differently? And I think that's a question that you have to ask yourself and if you feel actually you would have done things differently, what would you have done differently? What have you learned? And what's the learning you need to take out of that past collision before you can move forward? But actually many people who've spoken up, when you speak to them, they say "well actually I would do exactly the same thing". Or "maybe I might go through that thing slightly differently if I were to relive it but ultimately I felt an imperative to act to avoid that moral injury" and they felt they had no choice. So there's something about being compassionate for yourself and thinking about what are the barriers to letting go of that, to move forward, what is it that's so hard to let go of and why? And I think often it's things like the fantasy that good triumphs over bad. And ultimately that's the story that movies are made of, isn't it? That people, some small person takes on this huge organisation and brings it down on its knees. And the reality is that is not usually the story. That is not the story that happens for most people who speak up.

Naomi Murphy [01:07:16]:

And sometimes there's the idea that common sense is going to prevail if you can somehow explain your story in such a way that somebody's going to get what you're saying. And that somebody will then see the right thing to do and take action to do that. And again, sadly, I think often that doesn't happen for people.

But then also there can be things like emotions that we don't want to let go of. So what is the hook? If we're experiencing a feeling like shame, why is that so powerful for us right now? And why is it so hard to let go of that and move forward? Or other emotions like the grief, the loss, the sense of guilt. But I think ultimately moving forward requires us to be really honest with ourselves about what are the barriers to letting go. Why do I need to stay stuck in this chapter of my life? And what is going to help free me up and move on from this chapter of my life? How am I going to move into the next chapter? And I think about reflecting on what character are you playing in your own story? People can get stuck playing the victim. And obviously in a good story, the protagonist encounters some kind of obstacle, they overcome it and master it, and then they move on into the next chapter of the story. And if that doesn't happen, do you want to be stuck in that position of feeling like the victim for the next five years, ten years? How do you find a way to be the character in your own life story that you want to be? And I think sometimes people also really rush to embrace that role of hero. But often heroes are lonely in stories. Heroes are often the ones who have great moral courage but are also crying or unhappy. And the idea of being a hero can mean that you're setting yourself on a pedestal. That makes it very difficult then, for other people to come close to. And that might not be that you're looking down on other people, but it can contribute to other people feeling defective or ashamed that they perhaps wouldn't have had the courage to speak up in the circumstances that you've spoken up in.

And you could spend the rest of your life just choosing to interact with other people who have the same moral courage. But the reality is, for most of us, we'd have to shed quite a few people in our lives if we were to do that. Because lots of people "people-please" to find a way to make the situation as easy as possible. They don't have the same passion for their work or they look the other way. I think probably for all of us, or many of us, there were probably other people in the same circumstances that you were in. And other people perhaps knew things but didn't speak up. You were perhaps the person who stood up while others looked away. And that's not necessarily true for everybody, but I think that's often an experience. And so what have you learned from this crisis period in your life? What have you learned from this chapter? And that might be stuff that's for good as well as stuff that's for bad. And thinking about what was your identity prior to the crisis, prior to speaking up. What were your beliefs? What was your prior experience of authority figures? Because for most of us, our employers or our coaches, the organisation that we've related to or we've spoken up about at some level does represent authority. And that's why their tactics are so powerful, because they do have this power that we struggle to leverage up to.

And so thinking about how do you want your next chapter to go? How are you going to restore your dignity? And we've alluded to shame quite a lot during this conversation. And I think certainly the point to shame is that shame is supposed to make us hide and make us pull back from things. Well, actually, if you want to overcome that shame, then you have to confront it. And that involves being willing to kind of engage and have conversations. Many people who speak up, they act as if they have something to be ashamed of, even though that really isn't the case, because they've been tarred and feathered. They've been treated in such a way that that shame has really permeated them. So I think it's important to be honest with yourself about how much shame has permeated your life. How much have you allowed shame to restrict you and make life difficult for you and then think about how you manage to confront the shame and find a way to move forward.

And then I think, finally, your next chapter has to be written in a way where it's consciously constructed. And when you have been living through an experience that's so destructive, I think it's really important that what comes out of that is something creative, that you are able to think about what you can create from your experience. And that doesn't have to be in the field of working within the community of those who've spoken up. But find what's right for you. There are people who've written books about their experiences, and I think, again, there's a sense of ownership of your experience when you do that.

Des McVey [01:13:14]:

Garrick's work on toxic tactics is another very creative and a useful way for to be creative

Naomi Murphy [01:13:26]:

So there's something about how do you find ways to be creative and move forward and what have you learned and how do you apply that? Because actually it's possible to come through and be a stronger person, have hope again and create a future. The interesting thing about Bruce Feiler's book is, he interviewed lots and lots of people about their life stories, and many of them had experienced periods of really awful situations comparable with the kind of situations that people here might have experienced, maybe in some cases, much more serious and devastating. But actually, people found a way to make sense of their experience and move forward in a way that was constructive. And sometimes people were saying, "I wouldn't undo the fact that I have cancer, because actually, what this forced on me was a way for me to think about my life differently". So, we're not suggesting that people drop the part of their identity that's tied up in whistleblowing and speaking up and having moral courage. But what we're suggesting is it's much better if that's integrated into your identity rather than made an integral part of who you are, because that gives you more hope.

We really hope you’ve found this helpful and encourage you to give us feedback. We're really keen to hear about what people think about these ideas and whether that offers enough information to give people a sense that they can take some action and purpose in their lives. So we'd be really glad to have feedback if you have a few minutes to spare by hitting the button below