Listen to your body: have better health and relationships and live with authenticity

Rough text to accompany workshop at York Festival of Ideas (9th June 2024)

Introduction

Interoception is our sixth sense which can help us live much healthier lives, have better relationships and be more efficient at decision making. There’s even some research proving that it can make you rich. I will get to that shortly.

I’m interested in interoception because I specialise in treating symptoms of trauma and neglect. I also help people improve their wellbeing through the use of talking therapy and non-invasive technologies that calm the nervous system. And interoception is key to all this but if you’re just looking to improve your wellbeing or make better decisions, interoception could also help enrich your life.

How many sensory systems do we have?

All of us are familiar with our 5 sense perception of sight, sound, taste, smell and touch.

But we actually have 8 sensory systems.

In addition to interoception, our vestibular system creates the sense of balance and spatial orientation for the purpose of coordinating movement with balance.

Proprioception is the body’s ability to sense movements, location and actions

Are proprioception and interoception inversely related? I wonder if strength in one system might make us less attentive to another. I would say I’ve got pretty good interoceptive sensitivity but I have zero hand eye to coordination.

I’ve also worked with lots of athletes who obviously excel when it comes to proprioception but actually really suck at knowing what’s going on inside their bodies. This isn’t surprising when one considers how much athletes need to ignore what’s going on inside their bodies to keep going even when things feel tough.

It’s almost as if one of your senses is getting extra attention at the expense of another one. Which makes sense – for instance we know that when people lose a sense, like sight, other senses will over-compensate and we see changes in the brain in those areas that process sight and sound

What is interoception?

Interoception is detects the data that informs homeostasis.

Homeostasis is the process of maintaining the physiological parameters of a living organism within the range most conducive to optimal functioning and ultimately survival.

Our awareness of our inner feelings not only tells us to sleep when we need rest, eat when we need energy and drink when we are thirsty. It can also help us tweak and adjust our actions, prompts changes in our relationship to others and adapt our bodies to our environment. All in the interest of survival.

So interoception is this ability to detect what’s going on inside our body. It was interoception that told me I was nervous when I woke up this morning and felt fluttering in my stomach and my heart beating slightly faster than usual.

Interoception helps us recognise sensations such as pain, bodily temperature, itch, sexual arousal, hunger, thirst, heart rate, breathing rate, muscular tension, touch, tiredness and so on.

We’ve known about interoception for around 100 years, but it didn’t really get much attention until the last 15 years when a neuroscientist Bud Craig focused his attention on it. Craig noticed that interoception is not just about sensing feelings from our internal organs. It’s actually about sensing the entire condition of the body and helping it maintain its health and vitality. Craig proposed that interoception helps us achieve homeostasis.

Does homeostasis involve our emotions?

Homeostasis is the body’s drive to achieve an optimal internal balance using the least amount of energy possible across all environmental conditions and at all times. Being in balance helps us to be healthy and live longer and be less vulnerable to illness and disease. Using energy efficiently is key for survival of every living organism and is an essential and decisive determinant in natural selection.

We generally think of homeostasis as being concerned with our physical body, the state of our organs.

But in fact, thanks to the work of Bud Craig, we now know it’s just as crucial for how we feel emotionally. And we also know that our emotions have a really significant effect on our body.

We might know this from the way that some of our emotions are reflected in our language. We talk about being heart-broken, having a hot temper, a gut feeling, cold feet, we are quivering with fear or find our flesh crawling.

We know that people who experience difficulties in detecting and discussing their emotions tend to have more problems in processing them and we associate this with poorer physical health. It shows up in cardiovascular illnesses like heart disease and stroke, digestive and bowel problems as well as auto immune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

For a long time, we’ve assumed our brain is acting as the conductor for our bodies but we now know that there’s a second brain hidden in our digestive system known as the enteric nervous system. The two brains appear to communicate with one another sending messages back and forth. And our enteric nervous system sends as many messages to our head as our thinking brain sends to our stomach. We used to think that anxiety and depression contributed to digestive problems, but it’s increasingly looking like gut irritation may also contribute to anxiety and depression and even conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

I listened to the Huberman Lab podcast featuring Diego Bohorquez this week. He’s from Ecuador and researches the gut instinct. He discusses how when indigenous farmers historically planted crops using their intuitive knowledge of the land, they were typically drawn to plant crops in combinations needed for a healthy body – fibre, protein and carbohydrates.

Our third brain

The heart also has a brain. The intracardiac nervous system appears to have its own logic and whilst it receives messages from the brain, it also actually sends more messages to the brain than it receives. The heart-brain is capable of acting independently of brain signals to learn, make decisions and even feel and sense.

A growing body of research suggests that information coming from our heart has short and long-term memory functions and influences attention level, motivation, perceptual sensitivity and emotional processing.

Interoceptive sensitivity

Interoceptive sensitivity is our ability to detect the signals happening within our body, to differentiate between different visceral feelings and the ability to articulate them. People differ in their ability to do this.

When researchers explore interoceptive sensitivity they’ve tended to use people’s ability to count their heartbeats as a way of measuring how sensitive they are but people differ in what they have any sensitivity to within their bodies.

Some people are very interoceptively sensitive, others find it difficult to detect bodily signals. We often associate this with trauma. Others are over focused on one particular set of bodily signals such as those that might indicate anxiety and fear whilst being under attentive to feelings like love, joy and pride.

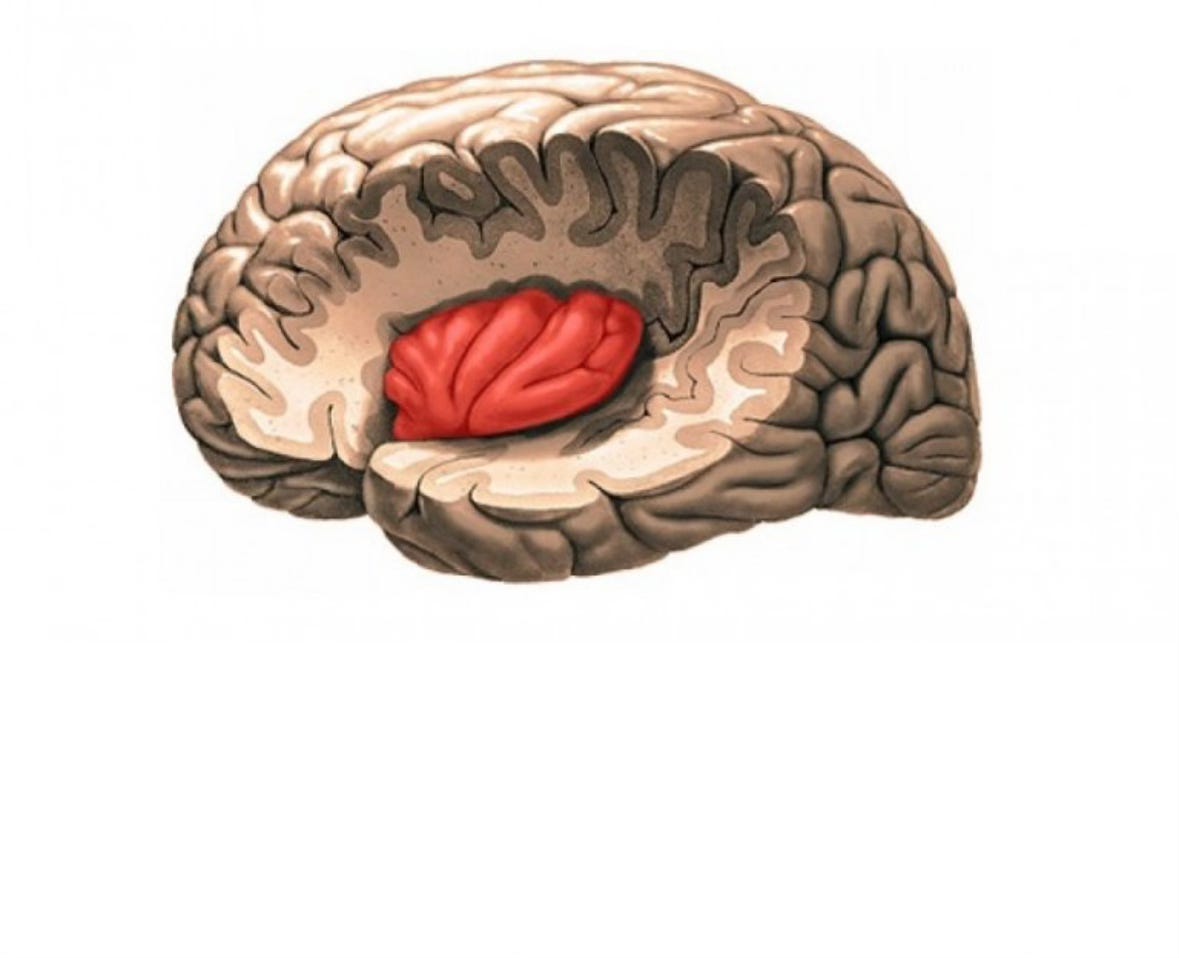

The role of the insula

The visceral feelings we have inside our body keep our brain informed, at least at a subconscious level, of its relative success at living, “at being”. The area of the brain that is most involved in processing information about the body is the insula.

The insula coordinates the information it receives from our stomach, our heart and our bladder and turns it into a message that we can identify on a conscious level. So it might translate a bodily state into signals we can read like “I’m hungry”, “I want sex”, “I’m in pain”.

Or it might translate the signals into an emotional state like “I’m angry”, “I’m happy” or “I’m excited”.

A properly working insula leads to greater sensitivity to interoceptive signals. People with greater interoceptive sensitivity have a thicker insula which is also more active.

How does interoception help?

Improves self-regulation

People who are more sensitive to their interoceptive signals tend to find it easier to self-regulate:

Bodily states (like temperature, anticipating when they need the toilet, knowing how much and what kind of food to eat, recognising when they are in pain)

Sensory regulation (when feeling overwhelmed, seeking out quiet; when feeling hemmed in, going for a walk)

Attention regulation (feeling distracted by background music, so turning it off; tidying desk to feel “uncluttered”)

Energy regulation (seek caffeine when needing energy; feel antsy at bedtime so take a hot bath to relax)

Emotional regulation (when feeling angry, explaining how we feel disrespected; when feeling sad, seek out comfort)

If you are able to recognise that you are feeling something, and discern what it is you are feeling, you are able to discern what action to take. If you can’t discern what you’re feeling, you might not choose the course of action that’s most appropriate.

I’ve spent 20 years working in prisons with men who have been violent. Many of these men found it hard to recognise when they felt hurt or sad and instead became angry. Anger can feel like a more socially acceptable, less emotionally vulnerable, more powerful emotion to feel than sadness, shame, fear or grief but produces a different behaviour than when we connect to our vulnerability. It gets an entirely different response from others too.

Better Problem Solving and Decision making

It warns us when there’s a potential problem and can help us detect what action to take. It helps us recognise when there’s danger or a threat in the environment (this is known as neuroception a distinct part of interoception). And enables us to feel more safe.

When we arrive in the world we have to make sense of our external surroundings. Over time we learn whether experiences make us feel good or bad. Our brain increasingly develops short-hand signals called somatic markers to recognise situations so that we can intuitively respond more quickly than we could if we have to spend time thinking about every action. These are very idiosyncratic and are drawn from our own experiences.

One study looked at the ability of traders on a London trading floor to detect their heartbeat. Those who were more easily able to do this performed better than matched controls. Their ability to detect their heartbeat predicted both their profitability and their duration in the financial market.

Interceptive information about the state of the body provides valuable feedback in decisions about risk even when we’re not consciously using it. It strengthens what we often refer to as a “gut feeling” even when the information may be coming from other areas of our body such as our heart, our bodily temperature, our breathing.

The more attuned we are to our bodies, the easier it is to draw on this information consciously to help us make decisions that work out well for us. The changes in our physiological state are known as “somatic markers” (Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis) and help us make decisions before we are able to cognitively identify why we’ve chosen this course of action. People differ in their ability to generate and detect these changes.

In this particular study, traders who performed best were more sensitive to these somatic markers and used this to inform their decisions. And they made more money.

Increased Empathy

The better we are at knowing how we feel, the better we are at knowing how others feel too.

Increased ability to connect and belong

Research finds there is an association between low interoceptive sensitivity and alexithymia. Sometimes called “emotional blindness”, alexithymia makes it hard to know or communicate what you’re feeling. This can affect your mental health as well as your relationship with others.

Emotion and feeling is what makes us vibrant. When people lack awareness of what they are feeling, they can come across as monotonous. It’s the emotional content of someone’s speech that often hooks us in, keeps us interested.

If you’re not sure what you’re feeling it can also be hard to know what you want or need. And if you don’t know much about yourself, how can others get to know the real you? So interoception helps us know about ourselves as well as helping us connect to others.

Even if you aren’t very interoceptively sensitive, you probably crave relationships with others, just like anyone else.

If we understand how we feel, and how others feel, it’s easier to find our tribe, our people who we connect and gel with. And its easier to recognise when we are conforming to the social rules of that group and ensure that we don’t end up outside the group.

How to improve your interoceptive sensitivity?

The good news is you can improve your interoceptive sensitivity, your ability to detect your own somatic markers, through practice.

- Listening to emotive music or watching emotive films and noticing what impact it has can be a good starting point.

- Practicing doing Body Scans like this one

- Focusing your attention on how you feel in your body when doing Mindful Breathing / Walking

- Noticing what it feels like when you cuddle a loved one or stroke a pet

- Yoga (especially slow-flowing yoga such as yin or restorative yoga or somatic yoga) is a great way to improve your awareness whilst also being good for your physical and mental health.

- Journalling focused on what you notice in your body

- Turning your attention inwards and noticing what you’re experiencing when you’ve had a good or bad day

- Practice asking your body for clues when you need to make a decision and choose between two options - does one option generate more tension in your jaw, raising of your shoulders?

Some talking therapies such as sensorimotor psychotherapy and somatic resourcing really focus in on interoceptive sensitivity and developing this as a way of improving emotional wellbeing. If you’re interested to know more, please feel free to contact me for a free online consultation.

Read more about interoception in:

Feeling and Knowing by Antonio Damasio

Interoception the Eighth Sensory System by Kelly Mahler

How do you Feel? by Bud Craig